December 15, 2021 — Both HTML and Markdown mix content with markup:

A link in HTML looks like <a href="hi.html">this</a>A link in Markdown looks like [this](hi.html).I needed an alternative where content is separate from markup.

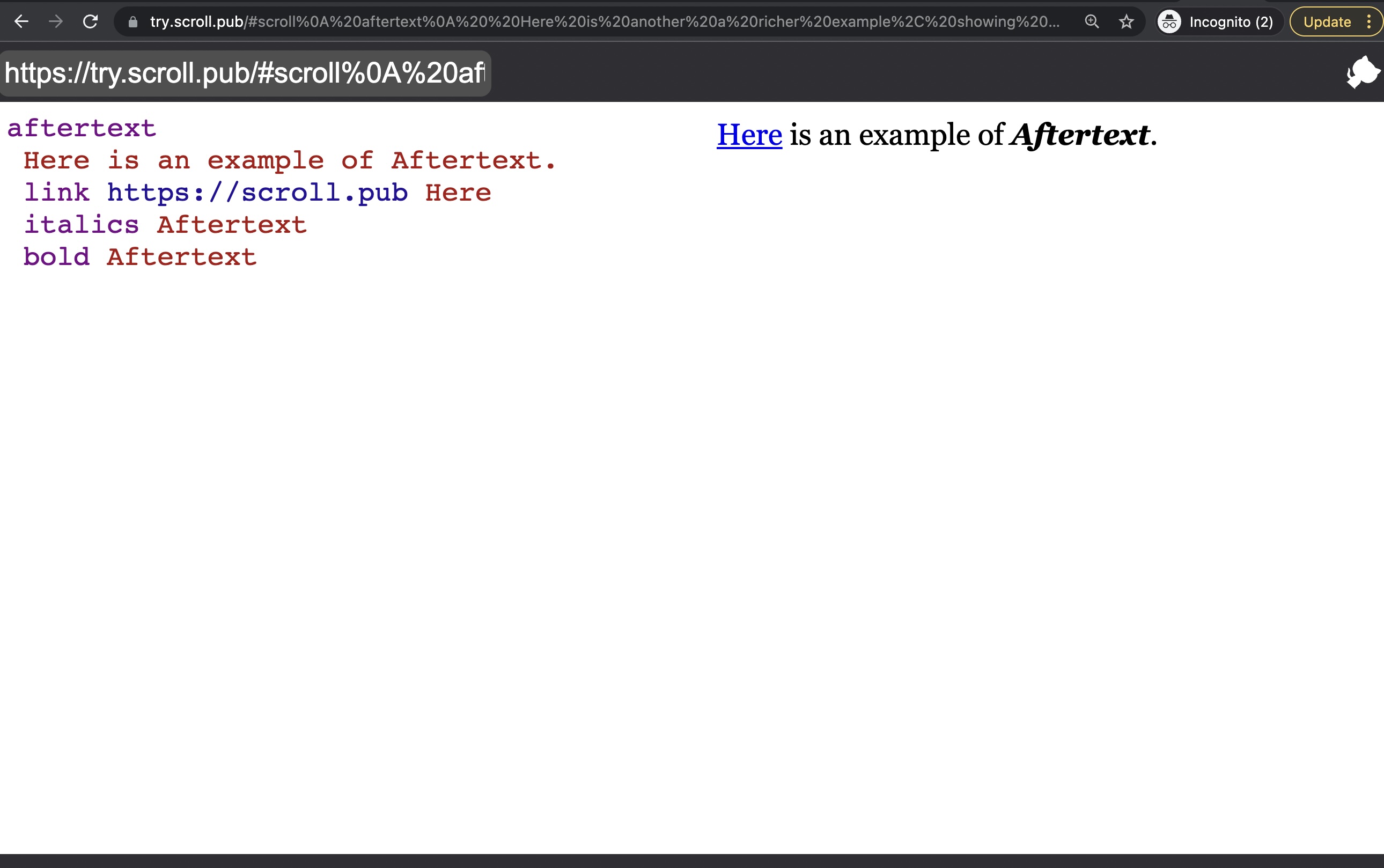

I made an experimental microlang I'm calling Aftertext.

A link in Aftertext looks like this.

https://scroll.pub thisYou write some text. After your text, you add your markup instructions with selectors to select the text to markup, one command per line.

Here is a silly another example, with a lot of aftertext.

Here is a silly another example, with a lot of aftertext.

strike a silly

italics a lot

bold with

underline aftertext

https://try.scroll.pub/#scroll%0A%20Here%20is%20a%20silly%20another%20example%2C%20with%20a%20lot%20of%20aftertext.%0A%20%20strike%20a%20silly%0A%20%20italics%20a%20lot%0A%20%20bold%20with%0A%20%20underline%20aftertext Here

The first implementation of Aftertext ships in the newest version of Scroll. You can also play with it here.

Why did I make this?

First I should explicitly state that markup languages like HTML and Markdown with embedded markup are extremely popular and I will always support those as well. Aftertext is a third way to markup text, there when you need it. The design of Scroll as a collection of composable parsers makes that true for all additions.

With that disclaimer out of the way, I made Aftertext because I see two potential upsides of this kind of markup language. First is the orthogonality of text and markup for those that care about clean source. Second is a fun environment to evolve new markup tags.

Benefits of Keeping Text and Markup Separate

The most pressing need I had for Aftertext was importing blogs and books written by others into Scroll with the ability to postpone importing all markup. I import HTML blogs and books into Scroll for power reading. The source code with embedded markup is often messy. I don't always want to import the markup, but sometimes I do. Aftertext gives me a new trick where I can just copy the text, and add the markup later, if needed. Keeping text and markup separate is useful because sometimes readers don't want the markup.

It is likely a very small fraction of readers that would care about this, of course. But perhaps it would be a set of power users who could make good use of it.

Speaking of power users, Aftertext might also be useful for tool builders. Imagine you are building a collaborative editor. With Aftertext, adding a link, bolding some text, adding a footnote, all are simple line insertions. It seems like Aftertext might be a nice simple core pattern for collaborative editing tools.

Version control tools are often line oriented. When markup and content are on the same line it's not as easy to see which changes were content related and which were markup related. In Aftertext, each markup change corresponds to a single changed line. In the future, I could imagine using AI writing assistants to add more links and enhancements to my posts while keeping the history of content lines untouched.

Finally, I should mention that it seems like keeping the written text and markup separate might make sense because it often matches the actual order in which writing text and marking up text happens. Writing is a human activity that goes back a thousand generations. Adding links is something only the current generations have done. A pattern I often find myself doing is: write first; add links later. Aftertext mirrors that behavior.

A Petri dish for new markup ideas

Aftertext provides a scalable way to add new markup ideas.

Simple markups like bolds or italics aren't a big pain and conventions like bold and italics used in languages like Markdown or Textile do a sufficient job. But even with those, after a certain amount of rules it's hard to keep track of what characters do what. You also have to worry about escaping rules. With Aftertext adding new markups does not increase the cognitive load on the writer.

When you get to more advanced markup ideas, Aftertext gives each markup node it's own scope for advanced functionality while keeping the text text.

I'm particularly interested in exploring new ways to do footnotes, sparklines, definitions, highlights and comments. Basic Aftertext might not be compelling on its own, but maybe it will be a useful tool for evolving a new "killer markup".

Adding a new markup command is just a few lines of code.

What are the downsides of Aftertext?

There are downsides in using Aftertext that you don't have with paired delimiter markups.

There is the issue of breakages when editing Aftertext. The nice thing about *bold* is that if you change the text between the delimiters you don't break formatting. When editing Aftertext by hand when you change formatted text you break formatting and have to update those lines separately. I hit this a lot. Surprisingly it hasn't bothered me. Not yet, at least. I need to wait and see how it feels in a few months.

A similar issue to the breakage problem is verbosity. Embedded markup adds a constant number of bytes per tag but with Aftertext the bytes increase linearly with N, the size of the span you are marking up. Again, I haven't found this to be a problem yet. Perhaps the downside is outweighed by the helpful nudge toward brevity. Or maybe I just haven't used it enough yet to be annoyed.

Another problem of Aftertext is when markup is semantic and not just an augmentation. *I* did not say that is different from I did not say *that*. Without embedded markup in these situations meaning could be lost.

What are the problems with the initial implementation?

My first implementation leaves a lot of decisions still to make. Right now Aftertext is only usable in aftertext nodes. That is a footgun. The current implementation uses exact match string selectors that only format the first hit. Another footgun. I've already hit both of those. And at least two or three more.

(Edit: these have been fixed.)

Is this a bad idea?

You might make the argument that not just the implementation, but the idea itself should be abandoned.

The most likely reason why this is a bad idea is that it simply doesn't matter whether it's a good idea or not. You could argue that improvements to markup syntax are inconsequential. That even if it was a 2x better way to markup text for some use cases, AIs will change writing and code in so many bigger ways that's it not even worth thinking about clean source anymore. This could very well be true (luckily it didn't take many hours to build).

Or perhaps it is a bad idea because although it may be mildly useful initially, it is actually an anti-pattern and instead of scaling well, will lead to a Wild West of complex colliding markups. I generally don't have the mental capacity to think too many moves ahead. So I fallback to inching my way forward with code and relying on the feedback of others smarter than me to warn of unforeseen obstacles.

Summary and Closing Thoughts

Markups on text may increase monotonically. With current patterns that means source will get messier and more complex. Aftertext is an alternative way to markup text which can scale while keeping source clean. Aftertext might be a good backend format for WYSIWYG GUIs. Though most humans write in WYSIWYG GUIs, Aftertext is designed for the small subset who prefer formats that are also maintainable by hand.

Related Work

Thank you to Kartik, Shalabh, Mariano, Joe and rau for pointing me to related work. I am certain there are similar efforts I have missed and am grateful for anyone who points those out to me via comments or email.

In 1997 Ted Nelson proposed parallel markup.

The text and the markup are treated as separate parallel members, presumably (but not necessarily) in different files.

When searching for '"parallel markup implementation"' I also came across a Wikipedia page titled Overlapping markup, which contains a number of related points.

A couple of folks mentioned similarities to troff directives. In a sense Aftertext is reimagining troff/groff 50 years later, when characters/bytes aren't so expensive anymore.

Brad Templeton describes two inventions, Proletext and OOB, to solve what he termed "Out of band encoding for HTML". They seem esolangy now but actually cleverly useful back in the day when bytes and keystrokes were more expensive.

The Codex project has a related idea called standoff properties. As I understand it, the Codex version uses character indexes for selectors which requires tooling to be practical and rules out hand editing.

AtJSON is a similar project and has clear documentation. AtJSON has a useful collection of markups evolved to support a large corpus of documents at CondeNast. AtJSON uses character indexes for selectors so hand editing is not practical.

Why now?

Issues with embedded markup and alternative solutions have been discussed for decades. I would say it's a safe bet to say embedded markup is superior since it so thoroughly dominates usage. Nevertheless, as I mentioned in my use case, there is a time and a place for alternatives. Aftertext would have been simple enough to understand decades ago and use with pen and paper. So why hasn't Aftertext's been tried before?

Verbosity is certainly a reason. Bytes, bandwidth, and keystrokes (pre-autocomplete) used to be more expensive, so Aftertext would have been inefficient. It probably was worthwhile to have a learning curve and force users to memorize cryptic acronyms. It paid off to minimize keystrokes.

I may also be overvaluing the importance of universal parsibility. I value formats that are easy to maintain by hand but also easy to write parsers for. Before GUIs, collaborative VCSs, IDEs, or AIs, there wasn't as much value to be gained by doing this. But even today I may be overvaluing hand editability. This seems to be the era of AIs and all apps editing JSON documents on the backend. I may be a dinosaur.

Finally, I may be overvaluing the clean scopes used by Aftertext provided by the underlying Tree Notation. Aftertext works because each text block gets its own scope for markup directives and each markup directive gets its own scope and you don't have to worry about matching brackets. So maybe Aftertext just hasn't been tried because I overvalue that trick.

Notes

- There's no reason it has to be "Aftertext". The markups could come before the text too.

- Thanks to justinpombrio for pointing out how semantic embedded markup is different than augmenting markup.

- Another downside of the current implementation, pointed out by David Chisnall, is the lack of a mechanism for global markup directives. I'd expect Aftertext to evolve in that direction if it proves its worth in the local scope.

A screenshot of Aftertext on the left and the rendered HTML on the right.